Peter Townsend was just 14 miles from completing a crossing of the Atlantic last week when he felt an unusual tremor run through the hull of his 47ft yacht, the Jubilate Mare. “You first feel a bump of the boat, as if you’ve run aground, or touched something,” says the British sailor. “Then we saw about five or six orcas.”

The 70-year-old yachtsman, a retired chartered engineer from Bristol who has been sailing most of his life, was off the coast of Tarifa in Spain with his partner, first mate Bee Bush, and two Australian crew members at the time.

“We had a hydrovane for self-steering at the back and they went for that, leaving it hanging off the stern. Then they started attacking the rudder, making the wheel swing with such force that it was dangerous to hold on to without breaking your wrists. The steering cables were stretched and pulled out.

“They stuck around the boat for about 20 minutes. There was a period of intense bashing of the rudder. One of the animals, which we assumed was the bull, was about 20 feet in length and must have weighed about three tonnes. My boat is only 17 tonnes – three tons of killer whale could do a lot of damage.”

“We were worried. There is conflicting advice on what you should do, and no definite technique to make the blasted things go away. We were doing an overground speed of about eight knots and they were easily keeping up.

“We were all on deck wearing life jackets. If they had pulled out the rudder there could have been a hole in the boat, and then water would have come in. Eventually they left and we managed to steer a wiggly course back to land.”

Townsend had made his Atlantic crossing with six other yachts, leaving the Caribbean in May. Two of the other boats in the fleet were also attacked. While Jubilate Mare has not been taken out of the water yet, he estimates repairs will cost thousands of pounds.

“Before this, I was sceptical about the attacks, thinking, ‘It can’t be true.’ It really opened my eyes to the damage they could do.

“We did a 42,000 mile round-the-world trip and spent a lot of time hoping to see the whales, and then the b—dy things attacked us on the last 14 miles. “Who knows why they did it? There are theories that they like the thrill of the wake, or of revenge attacks, but it’s impossible to judge whether it’s malice or playfulness.”

It is a question that is increasingly perplexing the sailing community, as reports of orca attacks proliferate. Since 2020, there have been more than 500 accounts of sailing and fishing craft being rammed, their rudders chewed off, or their propellers battered by the curious cetaceans.

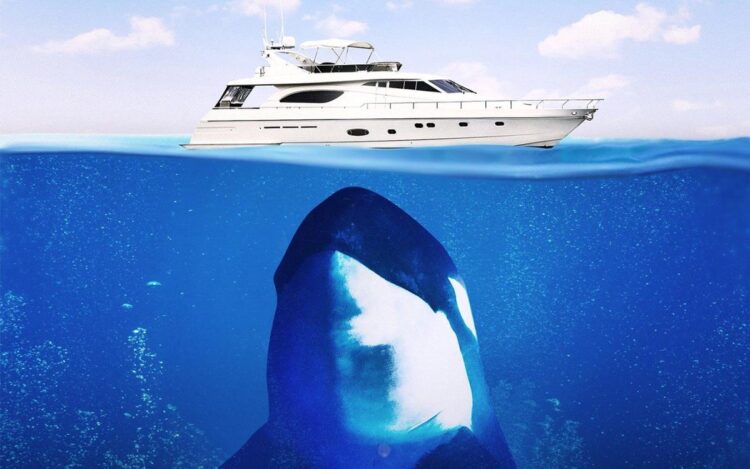

It is a sequence that is changing the perception of an animal that only a generation ago was celebrated for kindness towards humans in the film Free Willy, in which an orca befriends an orphan boy. Now, film associations veer towards Jaws. But is that fair?

Most attacks have occurred around the Iberian peninsula, off the coast of Spain, France and Gibraltar and in the past year alone, three vessels have been sunk. Just last week, two yachts taking part in the Ocean Race reported three orcas slamming against their hulls in the Straits of Gibraltar, while a yachtsman reported a killer whale ramming his boat in the North Sea between the Shetlands and Norway.

So, are orcas really hunting humans? Or is it simply that social media has made it easier to disseminate such attacks? Here are the best theories:

Nature fighting back

For a generation that grew up with Jaws, the fear of vengeful man-eating monsters lurking in the deep is seared indelibly into the consciousness of Western cinema-goers.

Apocalyptic “eco-noir” parables – in which nature turns against humans in retaliation for destroying the planet – are now commonplace tropes in the publishing and movie industries.

So it is perhaps unsurprising that one theory suggests that attacks are being committed by a vengeful pod of Iberian orcas, hell-bent on retribution for past harms.

Certainly, when Ester Kristine Storkson’s 37ft yacht was rammed by several killer whales off the coast of France last August she said it seemed like a “co-ordinated attack”.

Alfredo Lopez, a marine biologist from Aveiro University and the Atlantic Orca Working Group, believes a female orca named “White Gladis” suffered a collision with a boat off Spain – or became entangled in a fishing net – leaving her with mental trauma.

According to Lopez, the encounter “flicked a behavioural switch” bringing on aggressive behaviour which has since been passed to other members of the pod.

Last week it appeared the behaviour had spread further north, after Dr Wim Rutten, a 72-year-old retired Dutch physicist and experienced yachtsperson, claimed an orca had repeatedly rammed his boat off Shetland, creating “soft shocks” through the hull.

Others are unconvinced. For a start, no humans have been injured in any of the orca attacks, even though the creatures are more than capable of destroying boats and killing sailors.

Who can forget the BBC Earth episode showing a pod of killer whales working together to create a wave to knock a seal off an iceberg into the water, where it was quickly devoured?

Killer whales are not in fact whales, they belong to the dolphin family, and their name is a contraction of “killer of whales” – they are known to hunt whales many times larger than themselves.

So the missing human body count suggests there is no sinister motive behind the contact. Crucially, there has been no record of any contact with humans swimming from boats.

And the “traumatised orca” scenario only works if we take a human-centric view of the orcas, projecting human psychology onto animal behaviour.

Robin Mouatt, assistant manager at the VisitScotland iCentre in Lerwick said: “It seems like a conspiracy theory. There isn’t some killer whale out there with a grudge, that’s gone a bit Moby Dick.

“They are playful, interested in what is going on, but they never touch humans at all. Mostly they are just having a look and if what happened did happen, I am sure it would have been accidental.

“They are also clever creatures, so they may have realised that if they nudge the propeller they can make this floating thing stop, or go in a new direction. But they’re not out to get the pesky humans.”

Sailors taking part in the Shetland Race between Bergen and Lerwick, who left Norway in the same week as Rutten, said they had not encountered any orcas on the crossing and the UK Coastguard Agency said no incident had not been reported.

Fridtjof Bergmann, chairman of the Shetland Race said: “There has been no confrontation or damage. We’ve had orcas on the starting line one year, which was spectacular, but they weren’t a problem. There is nothing to scare people.”

Ascertainment bias – it’s nothing new

Italians Ambrogio Fogar and Mauro Mancini were sailing through the Rio de la Plata, between Argentina and Uruguay when a pod of orcas attacked their yacht Surprise, sinking the vessel in just four minutes.

The pair – en route to circumnavigate Antarctica – were left clinging to a raft for 74 days. Mancini, a journalist, eventually died awaiting rescue. The tale might seem reminiscent of recent reports of orca attacks, but it happened in 1978, proof that confrontations between sailors and killer whales date back decades at least.

Undoubtedly, incidents of orcas targeting boats have ramped up in recent years. In the days of Fogar and Mancini, the log book was the only method of recording a life-threatening encounter at sea.

In fact, their story only made it into the international press because Fogar was a famous adventurer and the survival story was extraordinary. The pair clung to a raft for more than two months, existing on rainwater, cockles and cormorants, which they bashed to death with their oars.

Today, even the most banal encounter can be circulated on social media within minutes, giving issues more weight than deserved because they are caught by ascertainment bias – a distortion in measuring the true frequency of a phenomenon, due to the way in which the data are collected.

The ‘Covid effect’

The pandemic also brought a surge in sailors. Like lockdown puppies and sourdough, boat sales increased by up to 30 per cent in the first quarter of 2020, according to the National Marine Manufacturers Association. And more boats means more chances of an encounter.

Most attacks happen near popular orca-watching spots, such as the Portuguese port of Sines where five people needed to be rescued when killer whales sank their boat last August.

Some tourist boats throw mackerel and herring to tempt orcas in for pictures, while fishing vessels often dispatch bycatch and fish guts, leading orcas to associate boats with food.

Wildlife expert Hugh Harrup, of Shetland Wildlife, said the Shetland attack was likely triggered by Mr Rutten fishing for mackerel off the back of his boat.

“There’s a clear association between orcas and herring and mackerel, so we shouldn’t be surprised when an orca approaches a smaller boat,” he told The Shetland Times.

Lopez told The Daily Telegraph that he believed Covid may have been a contributing factor.

“If the increase in boats implies an increase in tuna poaching, then yes. This behaviour is related to tuna fishing by sailboats,” he said.

During quarantine, dolphins were recorded bringing gifts of coral and glass bottles to the Barnacles Cafe and Dolphin Feeding Centre in Queensland, Australia, showing they were missing usual human interaction.

Anna Bunney, head of education at the marine conservation charity ORCA, said it was impossible to say for sure whether Covid could be related, but admitted the space of recent recorded encounters began in mid-2020.

“It’s tricky to blame Covid as the cause of these interactions, it’s possible they stretch back further and were unreported,” she said. “There has definitely been a spike in recent months, but it’s likely that as more reports are reaching the media and there is a wider public interest, and simply more attention on the attacks.”

Lissa Batey, head of marine conservation at the Wildlife Trusts, said: “I wondered whether Gibraltar might have seen an increase in boat traffic, and its reached carrying capacity.

“When there were a handful of boats, maybe the orcas were less fussed, there was enough space for everybody. Maybe there are now too many boats, and the orcas are defending their territory. More boats, more interactions. Or perhaps an individual has felt harassed by a yacht and they have lashed out to defend themselves.”

Orca fads

If ramming boats and munching on rudders seems like an unusual past-time, it is nothing compared with the dead salmon hat trend of 1987.

In the late 80s, conservationists in the Puget Sound area of the northeast pacific noticed that a female orca had begun carrying a dead salmon on its nose, a fad which quickly spread to the two other pods. The whales carried fish on their heads over a six-week period.

It was seen again a few times the following summer before completely dying out.

Killer whales are highly intelligent, and also rather faddy, exhibiting odd behaviour for a few months before moving on. Some orcas have been spotted latching on to the dorsal fins of larger males to hitch a ride, while in 2005, an orca in Marineland learned how to to catch seagulls using regurgitated fish as bait – a trend it passed on to fellow pod mates.

Recently, orcas in British Columbia have attacked crab pots, lifting and moving their anchors for no reason, while killer whales in the Salish Sea near Vancouver will harass porpoises.

Renaud de Stephanis, head of Spain’s CIRCE cetacean observatory, believes the young orcas may have developed a fondness for the bubbly disturbed water churned up by boat propellers.

Several have been spotted enjoying the high-pressure wake from propellers and Stephanis has speculated they may be ramming the rudder of sailing vessels to encourage the crew to turn on their engines.

“We think it is just a game for them,” said Stephanis, who is tasked with carrying out a report into why the orcas are attacking. He does not think they have malicious intent.

“If two or three killer whales really attacked a yacht, they would sink it in seconds,” he added.

Some sailors believe that orcas are intrigued by the rudders. Nick Withers, a contributor to the Orca Attack Reports Facebook group, said: “Where else in the ocean has the structure and movement of a yacht’s rudder?”

What next?

Whether the orcas really do have a grudge against humans, or are simply playing, the attacks are a headache for the tourism industry.

Foreign sailors are now avoiding Portuguese waters and going directly to Madeira and the Canaries. Those who stay are resorting to taking guns or firecrackers to scare away the killer whales, a strategy that is likely to increase tensions, perhaps eventually leading to a fatality.

The Portuguese Navy, the Institute of Nature Conservation and Forests and the ANC are trying to find a solution to the incidents, and are now considering an underwater acoustic device at popular sailing routes.

Like the salmon hats, the boat attack trend may soon disappear. What is clear is that the orca are not out to get humans, and leave once they have made the boats come to a halt. Almost all the attacks have been carried out by juveniles, suggesting rowdy teenage hijinks rather than a real desire to harm.

As David Neiwert, author of Of Orcas and Men: What Killer Whales Can Teach Us, recently put it: “They’re just orcas being orcas.”

For now, it probably is still safe to go in the water.

[ad_2]

Source link