Bigfork, Montana — As a sunset paints the sky pink on his Montana family farm, Jack Hanna sneaks a chunk of pizza to his golden retriever when a man approaches to greet him.

“Hi Jack,” the family guest says. “It’s a pleasure to meet you.”

The longtime zookeeper’s famous smile fades into curiosity.

“Where are you from?” Hanna asks between bites.

“Columbus, Ohio,” the family guest says.

Hanna built the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium into one of the nation’s best. He then captivated national audiences on David Letterman’s late-night talk show, “Good Morning America” and a number of his own Emmy-winning animal series that still run in syndication. He traveled the globe as a leading animal conservationist promoting Columbus. It was his home for decades. It’s even where he once said he wanted his ashes spread whenever he passes away.

But in this moment, none of that history feels familiar.

Hanna pauses, then asks a question.

“Have I ever been to Columbus, Ohio?”

The Jack Hanna the world once knew is gone.

At age 76, Alzheimer’s disease has stripped away his memory and the life he led in the public eye for almost a half century. He was first diagnosed in the fall of 2019 with early Alzheimer’s but now the disease has advanced to the point where he doesn’t know most of his own family.

Gone is the old Jack who enchanted nearly everyone he met with his Tennessee farm boy charm and endless funny stories. Gone are the khakis and the worn, leather outback hat that he made famous around the globe.

Q&A: Families combating Alzheimer’s disease are not alone. What you need to know

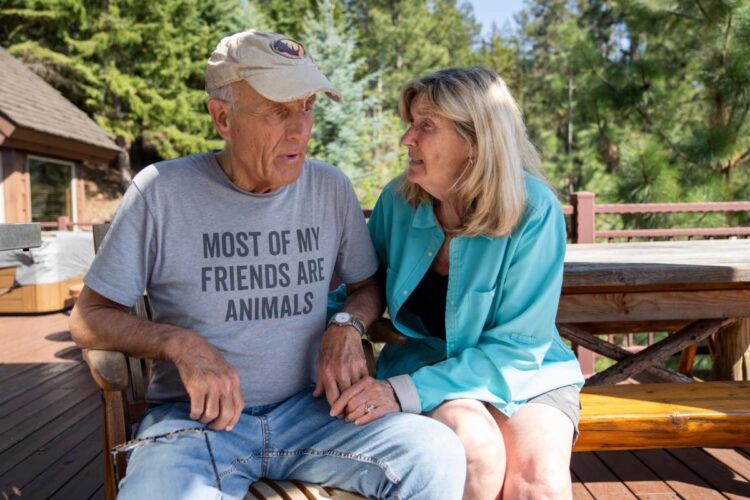

The Jack that remains now only remembers his wife Suzi, his dog Brassy and, at times, his oldest daughter Kathaleen when she travels nearly 5,000 miles from England to care for her dad. He spends hours baking himself in the sun on the back deck of his lakeside home. He asks Suzi a couple dozen times a day if she has fed the dog. He worries that the air coming out the vents might be hurting the house or the lights on the Christmas tree might catch everything on fire.

Once, Jack complained to Suzi that he had gone blind. He kept forgetting he had inserted his contact lenses and his doctor discovered he ended up with five in each eye.

Jack looks close to the same man who the public adored. But his frame is about 20 pounds lighter, his skin is a darker shade of tan, he wears black-framed glasses to avoid another contact mishap, and the eternal smile has been replaced by strained, vacant expression. On most days he dresses himself in jeans, a T-shirt, and an old, tattered tan baseball hat with a rhino patch from his time working at the Columbus Zoo.

The couple of 54 years used to travel the world together, but for about two years, their life has been contained to a 30-mile radius in Northwest Montana centered around their house and 50-acre farm.

In Jack’s mind, even the slightest change to his daily routine is the enemy. The continuity of his routine calms a man who has little memory of his previous life. Disruptions to it can cause outbursts of frustration or even anger, usually toward Suzi.

He and Suzi live the same day over and over. Jack is restless at night and often doesn’t fall asleep until 2 a.m. or later — a common experience for those with Alzheimer’s. He rises mid-morning and eats the same breakfast — a bowl of blueberries, three scrambled eggs with cheese in the middle, bacon, tomatoes and two waffles with butter and lots of syrup. They take a late-morning, two-mile walk. And until very recently, they would visit their farm to feed their two donkeys, but the upkeep is simply too much, so the farm went up for sale last month. There isn’t much else to their days except for Jack slowly moving around the house constantly checking the front door to see if it’s locked or inside the washing machine but no one knows why.

“My husband is still in there somewhere,” Suzi said. “There are still those sweet, tender moments — you know, pieces of him that made me and the rest of the world fall in love with him. It’s hard. Real hard some days. But he took care of me all those years, and so it’s my turn to take care of him.”

This is the first time the Hanna family has spoken publicly about their struggle with a disease that afflicts an estimated 6.7 million people in the United States, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. There are about 24 million people worldwide living with Alzheimer’s, according to the National Institute on Aging (NIA). It is the seventh leading cause of death for adults in the U.S. and is the most common cause of dementia among people over 65, according to the NIA.

The Hannas are telling Jack’s story because they want other families to know they are not alone when the struggle with Alzheimer’s feels overwhelming.

“If this helps even one other family, it’s more than worth sharing dad’s story,” Kathaleen said. “He spent a lifetime helping everyone he could. He will never know it or understand it, but he is still doing it now.”

One walk at a time

A few steps into their daily hike on the river trail about five miles from his home, Jack stops at the first tree he sees.

“Hello tree, you are a pretty tree,” Jack says. “I love you tree. God bless.”

A few steps later he touches the leaves on the next tree and holds his hands out in front of it like a preacher performing a blessing in church. What it means only Jack knows.

A few steps after that, he touches another three. Then another and another. Sometimes Jack tempts fate and scares both Suzi and Kathaleen by reaching too far over the rocky, tree-lined ledge where the Swan River races about 50 feet below.

Jack is asked why he touches all the trees, but he just says he loves them and continues down the path.

Suzi said the scene repeats itself nearly every day. It takes more than an hour to go a mile due to all the stops, but Suzi, who is 75, doesn’t care. Jack can still walk pretty well for a man with two knee replacements and Alzheimer’s, and the hikes remind her of the life they used to have. The life that took them all over the world together, giving them experiences with both animals and people from cultures around the world that they couldn’t dream about when they fell in love as college sweethearts at Muskingum College.

“I want to hold on to these walks as long as I can,” Suzi said. “I remember the day this all officially started. The day the doctor told us what it was. I’ve just tried to hang on to the little pieces of Jack since then.”

It was Oct. 3, 2019 when Jack Hanna started shaking his head back and forth in defiance the instant Dr. Douglas Scharre told him he had Alzheimer’s disease.

“No way,” Jack said. “I don’t have that.”

Jack had every rationalization at the ready.

It was just old age. He was famous, even beloved, for his 20-second attention span. He always knew he had attention deficit disorder. His life went 100 mph. He was used to traveling more than 200 days a year. All those tests the doctor had him take must be wrong. Jack always said he was never good at taking tests in school.

Scharre, a neurologist and Alzheimer’s specialist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, was kind and positive while explaining the diagnosis to Jack, Suzi and their daughters, Julie and Suzanne.

Scharre explained that the mild cognitive impairment had transformed now into full Alzheimer’s. He told the family there was no doubt in his mind that the symptoms that he traced back to 2017 were Alzheimer’s.

Julie cried in disbelief. Suzanne hurt for her dad but wasn’t surprised at all because she had seen symptoms in the past year. Suzi did what she could to comfort Jack, but his mood quickly darkened.

He lowered his head, stared at the floor and continued to cast doubt on the diagnosis as the devastation set in.

“I know my brain doesn’t work so good sometimes, but I’m OK,” Jack said. “No way I got this.”

Jack didn’t use the word Alzheimer’s that day.

In fact, he has never uttered it, and those around him didn’t dare use it either.

Jack didn’t want the world to know.

And when they went back home that night, he made Suzi promise no one outside their family would ever find out.

Suzi said Jack was worried that if the public found out he had the disease his career would be over, and he wasn’t ready to stop working.

“People will think I’m dumb, Sue,” Jack said. “We can’t tell anyone Sue. Promise me.”

Suzi vowed to her husband she would keep the diagnosis secret.

The family didn’t ask Scharre about life expectancy. But the Alzheimer’s expert said that people with Jack’s diagnosis live typically between eight and 12 years after first showing symptoms.

Scharre said Jack’s reaction was not out of the ordinary.

“It was fairly typical, nothing dramatic,” Scharre said. “Most Alzheimer’s patients have a bit of denial. The thinking is, ‘Yeah, I am a little forgetful, but so is everyone else.’”

But the reality is those within Jack’s world already suspected he had something much more than forgetfulness in the months before his diagnosis.

Jack’s family and friends said there were times leading up to the diagnosis when Jack would forget what city he was in or what he was doing that day. When he would get on stage for his traveling animal shows, he would sometimes forget names and even details about the animals that were his life. Few on the planet had more passion for educating the public about the animals and taking them to their habitats through the power of his television shows.

There was another time in early 2019 when he was supposed to introduce an old friend who was receiving an award. But when he got on stage, he forgot why he was there.

His family, friends and those who worked with Jack would cover for him by speaking for him or reminding him where he was or what he was supposed to be doing at that moment.

They were used to Jack’s mind racing from one thing to the next without worrying about details, but this was something different.

Guy Nickerson, Jack’s longtime friend and business partner, first noticed Jack’s decline while they were producing some of the last episodes of Jack’s popular “Into the Wild” television show in the fall of 2018. On a trip in Rwanda, Nickerson explained to Jack all of the details of who they were meeting and when they were going to see the gorillas. Three minutes later, Jack asked Nickerson the questions he had already answered. Suzi constantly tried to cover for him during filming but there was only so much she could do.

On Jack’s last major international trip to South Africa in November of 2019, Nickerson said the man he considers to be somewhere between a father and a brother due to the close relationship, just wasn’t there anymore.

“We had an interview set up with a legend in the animal world and a good friend of Jack’s, and when it started, Jack didn’t know who he was talking with,” said Nickerson, who lives in Tampa.

“I never said a word to Suzi or Jack, but that felt like the beginning of the end. I didn’t know about the diagnosis until the rest of the world, but I knew something medically had to be wrong. I love Jack so much; it was so hard to watch all of that.”

Shortly after the Alzheimer’s diagnosis, Hanna quietly started making plans to retreat from public life. His last theatre performance with animals on stage was in March 2020, and the COVID pandemic canceled about a half dozen more shows. He publicly announced his plan to retire from the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium after 42 years in June 2020. He formally retired on Dec. 31, 2020.

Back on their river trail walk, Kathaleen tears up recalling how hard it was for her parents to give up their public life while hiding the reason for it.

“He would have worked until the day he died. He only retired due to the Alzheimer’s,” Kathaleen said. “He was embarrassed by it. He lived in fear the public would find out.”

‘My teeth are fine’

The second Jack Hanna hears the word dentist, he gets back in the car.

Jack needs a permanent crown on one tooth and a cavity dealt with on another.

He won’t budge from the car seat until Suzi lies to him. She convinces him that she is the one who needs to see the dentist, and he is going to hold her hand.

The soft, caring husband comes out for a few minutes until Jack sees the dentist chair.

He knows he is really today’s patient and glares at his wife.

“Sue, my teeth are fine,” Jack says in a rising voice. “Let go home. We have to feed the dog.”

Suzi and the dentist coax Jack into the chair, where he continues to protest over and over.

Suzi holds Jack’s hand as the dentist inserts the needle into Jack’s gum.

The dentist uses the same gentleness he would with a toddler, but Jack squeals in pain and tries to get out of the chair until Suzi calms him and the numbing takes hold.

Suzi and Kathaleen each take shifts comforting Jack, who manages to stay in the chair for more than two hours while his teeth are fixed.

Suzi hates seeing her husband in pain and hates lying even more, but the family has been through far worse.

“If we can get through the week we had a couple years ago, we can get through anything,” Suzi said. “I’m so glad Jack didn’t know what happened. It would have crushed him.”

Perfect storm

On March 25, 2021, doctors removed another tumor from Jack’s daughter’s spine, fearing if they didn’t, she would no longer be able to walk.

Julie Hanna almost died from leukemia in 1977 when she was two years old. Jack has said helplessly watching doctors try to save her while watching behind a glass wall was among the worst moments of his life.

The primitive radiation available back then saved Julie Hanna, but it has caused a lifetime of chronic pain, tumors and surgeries.

But this time, her father wasn’t able to even be at the hospital. The Alzheimer’s had advanced to the point where Jack didn’t really understand what was happening to his youngest daughter.

Then, as Julie continued to suffer severe pain, the Hanna family was suddenly thrust into a new fight — this one for Jack’s legacy.

On March 29, 2021, The Dispatch reported that Tom Stalf, former zoo president and CEO; and Greg Bell, former chief financial officer, resigned after an investigation by the newspaper detailed their extensive personal use of zoo resources. The zoo’s board eventually conducted forensic audits, which confirmed improper spending and questionable business practices by the former top two executives, resulting in more than $630,000 in zoo losses. Stalf and other top executives eventually agreed to pay back hundreds of thousands of dollars to the zoo.

Hanna hadn’t been an active director of the zoo since 1992 and wasn’t directly involved in the zoo executive controversy.

But he did have a close relationship with Stalf. And he helped Stalf join the zoo as its chief operating officer in 2010.

Julie, who is now 48, was finally released from the hospital on April 3, 2021 and taken to the Hanna family home just outside the zoo.

While the family cared for her and tried to digest the zoo controversy, the next blow was delivered.

The Hannas learned on the morning of April 5, 2021 that a new documentary called “The Conversation Game” was being released to the public. It alleged that the baby tigers and snow leopards that sat in Jack’s lap on late-night talk shows often didn’t come from the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium and didn’t end up there when the cameras stopped rolling.

Instead, the documentary says, the animals were shuffled among backyard breeders and unaccredited roadside zoos that were compared to “animal prisons” in some cases. The filmmakers say Jack and other celebrity animal conservationists actively misrepresented where the exotic cats came from and where they were going, leading the public to believe they were moving between accredited facilities.

The Columbus Zoo eventually lost its accreditation for almost 18 months as part of the fallout.

In the view of some close to the Hannas, the documentary made it seem like Jack didn’t care if animals were being taken from and returned to places where they were abused or neglected.

The next two days would be among the worst the Hanna family said they ever experienced.

There were tears and anger and debates on how to handle it all.

Kathaleen, the protector of the family, wanted to rush out in front of the television cameras and defend her father. But others thought that would only add more fuel to the story. They decided not to watch the documentary — ever.

Kathaleen said Jack wasn’t aware of any of the controversy.

“It was hell — absolute hell,” Kathaleen said. “He would never knowingly allow animals to suffer. They created a narrative around my dad that isn’t true, and he couldn’t defend himself. My dad would have faced all this head on like he always did. In hindsight, we all wish things had been handled better by the people working with my dad. And yes, it’s fair to say my dad should have known more about the animals. But he was always moving so fast. He would have wanted every animal to be safe and returned to a safe environment. He dedicated most of his life to protecting animals. It was all so heartbreaking.”

Jerry Borin had a front row seat for Jack the showman for almost 40 years.

They met back in 1984 when Jerry was working in the Columbus Parks and Recreation Department and Jack was transforming the Columbus Zoo from a dilapidated place few visited to a world-class destination for those who loved animals.

Borin was the zoo’s executive director from 1993 to 2008 and then after the zoo executives resigned in 2021 Borin was brought back to be the zoo’s interim CEO for about eight months.

Borin said when he returned to the zoo in 2021, he stepped into a mess surrounding the accreditation issue.

He said the records or paper trail left behind by those who were responsible for acquiring and tracking the animals was “not good.” He said it’s fair to criticize his long-time friend for not paying attention to where some of the animals he used on television came from.

“The records I saw weren’t good,” Borin said. “Jack just didn’t do details. But I don’t think Jack knew what was happening. If someone had told him face to face the animals were coming from unaccredited places, I believe he would have fixed it. It was a massive crisis for sure, but the zoo has recovered and is thriving.”

Jack had no idea the controversies were unfolding, and family members took turns keeping him away from the television. But one evening, Jack saw his own picture on the screen and started riddling Suzi with angry questions.

He thought Suzi had betrayed him and told the media about the Alzheimer’s.

“He just kept saying, ‘Sue, you told them, didn’t you? You promised me Sue, you promised,’” Suzi said. “It would have broken Jack’s heart to hear what was going on at the zoo. If we had tried to tell him, he wouldn’t have understood.”

But finally, with some demanding a public response from Jack, the family decided they had no choice.

It was time to tell the world about Jack’s Alzheimer’s. And, yes, the family was aware that some would accuse them of exaggerating Jack’s condition as a way to hide from the media.

Kathaleen had lobbied for a long time to go public, but Suzi didn’t want to betray Jack’s wishes. His legacy, however, was more important.

On April 7, 2021, the family issued a short statement announcing that Jack had Alzheimer’s.

In the following days, the Hanna family heard from many offering their sympathies.

That included the celebrity Jack was associated with the most — David Letterman.

On that call with Letterman, Jack retold a famous story about a beaver from the show. He repeated it to Letterman about four times.

Letterman understood what the family was dealing with and at one point used the word Alzheimer’s while the call was on speakerphone. That caused Suzi to run into the other room, fearing her husband would hear the word they never used.

To this day Jack doesn’t know his family told the public he has Alzheimer’s.

“It killed me,” Suzi said, “to break that promise.”

Family therapy

The four women to whom Jack devoted his life are all crying when he takes a mid-afternoon break from the Montana sun and shuffles back into the kitchen.

His wife Suzi is sitting at the table with Kathaleen, while Suzanne and Julie are on the phone from Suzanne’s home in Cincinnati.

Jack takes a seat at the end of the table and starts eating a bowl of grapes. He is oblivious to his daughter Suzanne talking about what it feels like to be the first forgotten by him.

His wife and daughters said Jack’s Alzheimer’s has now gone from moderate to advanced.

“He just stopped remembering who I was in all ways,” Suzanne tells her mom and sisters. “Whether it was in person or by phone, he had no idea I was his daughter. I think it’s because he didn’t see me as much because I got married so young and I moved away.”

Suzi hears the pain in her daughter’s voice and attempts to see if Jack can remember Suzanne.

“Jack, Suzanne is on the phone. She is your daughter; can you say hello?” Suzi asks. “Can you tell her you love her?”

Jack has no clue who is on the other end of the phone. But eventually he speaks.

“I love you too, sweetie,” he says. “Have fun.”

Suzi is now sobbing and tells Suzanne she wishes she was there in Montana to give her a hug.

What they dubbed family therapy continues for hours.

They share raw feelings with one another they never have before.

The responsibility of caring for Jack around the clock weighs on all.

Julie feels helpless that her own health problems prevent her from caring for her dad.

Suzanne, 50, has four grown children and helps care for Julie and wishes she could make more trips than she has to Montana. Her dad hasn’t been able attend two of her kids’ weddings nor has he met his only great grandchild.

Kathaleen, 53, who appeared with her dad on his television shows as a young girl, has two teenagers and a husband back in England. She has traveled across an ocean more times than she can count, juggling two lives to help Suzi care for her dad.

Suzi is reluctant to share with her daughters how hard it is to care for Jack alone, not wanting them to think she can’t handle it. The night Jack threw his back out, for example, he couldn’t get off the floor and Suzi struggled to get him up alone.

Jack takes several medications multiple times a day to combat his Alzheimer’s symptoms. Tracking all of them and making sure he consumes them is a part-time job by itself for Suzi.

Yet, Suzi refuses to let home health care providers come in and help her when her daughters can’t be there.

This frustrates and even angers Kathaleen, who has begged her mom for more than a year to get help. Kathaleen has even arranged for more help, only to have her mom cancel it.

“Mom you are 75 now, this is killing you,” Kathaleen says to Suzi. “Let us give you some more help. We have the money. And you need this.”

Suzi brushes aside the plea.

Kathaleen turns to her sister Suzanne for backup, but she doesn’t wade into the loving brawl.

“I am Switzerland,” Suzanne says. “Remember?”

“That’s why you are the favorite,” Suzi says, which sparks laughter from all three daughters.

“Thank God we all get along, right?” Kathaleen says in between tears.

Throughout it all, Jack stares out toward the beautiful lake and is halfway through another bowl of grapes.

“I just want it to be your dad and I for as long as I can,” Suzi said.

Lasting legacy

The morning is about half over when Jack emerges from his bedroom bare-chested, wearing only jeans and a heavy lathering of shaving cream on his face.

He stops, looks around the room and flashes a sheepish smile at Suzi and his guests, who can’t help but laugh.

This is a planned performance; one he repeats from time to time pretending to be Santa Claus.

“The showman is still in there somewhere,” Suzi said. “Jack loved making people laugh as much as he loved taking care of animals.”

There was a time when Jack couldn’t take three steps in Columbus or almost anywhere else in the world without someone asking for an autograph, wanting a selfie or telling him that they watched him on television while they were growing up.

At the Memorial Tournament in Dublin, Ohio, Jack would get more attention from the fans than the famous golfers — even Tiger Woods.

And Jack would have a pleasant greeting or more for every single person who approached him. Their age or skin color or cultural background didn’t matter to Jack. And he left no one out. If he signed autographs for servers in a restaurant, he would walk back into the kitchen to say hello to the cooks and dishwashers.

“Jack’s legacy is that he was one of the greatest animal advocates the world has ever seen,” said his friend Borin. “He might have done more to help people than the animals. And the public still loves Jack for all of it.”

Now when Jack walks into a restaurant in or near this Montana town of about 5,000 the locals might offer a friendly hello, but they give Jack and Suzi their space. Those who know Jack is living with Alzheimer’s wait for the right moment to give Suzi a hug of support and tell her to hang in there as the main caretaker.

Shortly after finishing his second piece of cheesecake Jack is eager to head back home.

He is worried Brassy doesn’t have enough food and wants a few more hours of baking in the sun.

Suzi caresses her husband’s forehead to counter the anxiety.

Alzheimer’s is commonly called the long goodbye as family and friends watch their loved one slowly fade away over time. Suzi has no idea how much longer her goodbye will last with Jack. She tries not to think about the more difficult days ahead — or when it might end.

“The river, the sun, Brassy, our walks. … That’s what we have left,” Suzi said. “The Jack people knew isn’t here anymore, but pieces of my husband are. And I’m going to hang onto them for as long as I can.”

@MikeWagner48

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Jack Hanna: How Alzheimer’s is stripping away the man the world knew

[ad_2]

Source link